Conor McPherson's The Weir - Quietly Homeric

Watching a

different production of a contemporary play was a novel experience for me. Nearly

fifteen years had passed since I first saw The Weir. How different would this

second viewing be, and what would a decade and half of cultural wanderings add

to the experience?

I first saw Conor McPherson's The Weir when it was first staged back in the late 90s, and my diary records some insubstantial and unengaged thoughts.

"Me and GJ watch a play called The Weir at the Duke of

York Theatre. Moody and atmospheric it

involved Irish characters telling ghostly stories in a pub. I thought it was a bit hit and miss, whilst GJ

found it odd and dreary. We grabbed some food at Bella pasta afterwards, where GJ, of course, found his pasta too

dry."

So, a real lack of detail from me, choosing instead to

dwell on GJ's culinary preferences rather than explore exactly why I found

the play 'hit and miss'. What was I liking; what did I dislike? Truth be told,

I suspect that I didn't quite get it. On a second viewing though I found The Weir wonderful. Here was a play that smouldered with regrets and passions expunged;

hilarious and sad, sometimes at the same time; full of Joycean paralysis and

the bar-room hilarity of Roddy Doyle at his best. The performances were

note-perfect, a lovely awkward chemistry filling the stage. You left the

theatre feeling slightly drunk, as if you too had in fact just spent an evening

in a rural and isolated Irish pub.

|

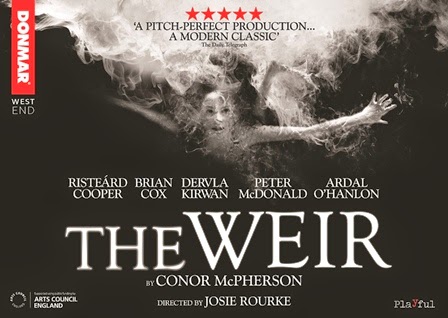

| The Weir cast (left to right): Peter McDonald, Brian Cox, Ardal O'Hanlon, Risteard Cooper, Dervla Kirwan |

Reading back my own initial thoughts left me even more confused. What had I missed the first time around? What did other people think? Would anyone react to this Weir in the way that I had done to the earlier one? I sought out the reviews - very well received - and then dipped ‘below the line’ - a favourite pastime - to see what the general public thought. Perhaps someone would come to the aid of my earlier puzzled self. There was, indeed, a real split between those who loved it and those who were left cold. The following comment, though, caused me to delve deeper:

"Utterly tedious. Did the critics go to another play

called The Weir that was the polar opposite to this pap? A pointless story, poorly told, dully staged

and not particularly well acted. Brian Cox has clearly employed Russell Crowe's

voice coach; his Irish accent was all over the shop. Very off-putting. Dervla

Kirwan's big speech is excruciatingly awful. It's like she's reading it from

cue cards. Ardal O'Hanlon is the one bright spot, albeit a very dull bright

spot. I spent most of the second half of the play wondering if I'd fallen

victim to some massive spoof, thinking surely nothing this bad could make it on

to the West End stage? But it wasn't and it is."

Aside from the problems with Brian Cox's accent - a

common criticism from the naysayers, and one that I didn't detect - the aspect

of this that got me thinking was the reference to 'cue cards' and Dervla

Kirwan's performance. Kirwan plays Valerie, a Dubliner on the brink of moving

to the remote rural location where the play is set. Shown around by Finbar, a

brash businessman, they find themselves sharing an evening in the pub with the

landlord Brendan, car-mechanic Jack, and his assistant Jim. Jack, Finbar and

Jim each tell a ghostly tale, which is then followed by Valerie's own story concerning her young daughter’s tragic drowning at the local

swimming pool. It is the way that Valerie tells this story that seems to have

rankled the above critic the most.

For me though it was spell-binding. And yet, I'd partially agree with the critic,

that there was an element of 'cue cards' about the monologue. But only because

this is, indeed, the way we tell those stories that stick with us, those that

we tell others - and ourselves - over and over again. Homer's oral tradition

paved the way for how stories are remembered and told. In the days before near-universal

literacy, when things were not written down and were spoken out loud around the

fire, poets had to remember tales in other ways. They did this through

mnemonic techniques, repetition of key lines and tropes, the same ways of

describing a character or a temporal change - grey-eyed Athena, swift-footed

Achilles, crafty Odysseus, rosy fingered Dawn – a ritual made up of verbal

building blocks that are then embellished with detail. Likewise, the characters

in The Weir are doing something similar.

|

| Rembrandt, Homer (1663) |

Ritual and repetition are the glue that binds the way that these characters talk to each other. The following is a routine repeated three or four times in the play:

Jack: “Are you having one

yourself?”

Brendan: “I’m debating whether to

have one?”

Jack: “Ah have one and don’t be

acting the mess.”

Brendan: “Go on then.”

And there is certainly an element of this when Valerie

tells her story, one concerning the cruellest and most painful blow of all, the

loss of a child. How many times had she repeated and rehearsed this story in

her head? How many more times will she tell it? Even in a single day, she would

be telling herself this tale over and over again. No wonder it comes across as

rote, as if read of a set of cue cards, a set of inescapable cards that occupy

her every waking moment. What could she have done differently? How could things

be otherwise? Every time she tells it, she must feel on trial. Telling it

over-correctly, trying not to make a mistake, pausing to remember the tiny

moments of hope where things may have been different, grasping for those cue

cards in case she is found out. In case

she finds herself out.

“But when I got in, I saw that

there was no one in the pool and one of the teachers was there with a group of

kids. And she was crying and some of the

children were crying. And this woman,

another one of the mums came over and said there’d been an accident. And Niamh had hit her head in the pool and

she’d been in the water and they’d been trying to resuscitate her. But she said she was going to be

alright. And I didn’t believe it was happening. I thought it must have been someone

else. And I went into, a room and Niamh

was on a table. It was a table for table

tennis, and an ambulance man was giving her the … kiss of life.”

|

| Storytelling: "You have to relish the details!" Dervla Kirwan and Brian Cox |

Remember the furore about the parents, particularly the mother, of Madeleine McCann. That 'maddened' and 'cold' and thus ‘guilty’ look in her eyes as if she wasn't telling the truth. Perhaps she herself couldn't believe the truth. Perhaps the guilt of leaving her small child unsupervised coursed through an overwhelmed consciousness and didn't spare her the energy to act 'naturally'. No wonder these tales come out as if they have been rehearsed. They have. They never stop being rehearsed.

Even GJ and his pasta preferences have something of this;

if we went out for an Italian meal tomorrow someone would be sure

to bring up the adjective 'dry' even before the menus have arrived at the

table, sparking the usual jokes and ribbing.

I didn't get The Weir all those years ago. I just wasn't ready for it. I thought it was a play about ghost stories when really it was a play about how we tell those stories, using techniques as old as

Homer himself. If we tell them well,

they are remembered and told over and over again. And if they are our most personal and most affecting stories, it's not just others that we are telling them to, it is ourselves.

Comments

Post a Comment