Madame Bovary c’est nous!

It is difficult for a seasoned reader to approach

Gustave Flaubert's Madame Bovary for the first time and not know of its

thematic touchstones. It is the great novel of adultery and

disappointment. It is a novel that is stamped with the word 'death'. You know it won't end well. This was certainly my sense

twenty years ago when I first read it. I enjoyed it and admired it

immensely, and subscribed, rather axiomatically, to the opinion that it was one

of the greatest novels ever written. But it has taken a second reading to

feel the irresistible pull of that latter claim. Nabokov is correct, we

don't read a book, we only reread it. Madame Bovary is glorious

and with few peers in the Nineteenth century - George Eliot's Middlemarch maybe - and I

will certainly try to give it a third read before I die.

That last remark is, perhaps, borne out of the mood that the novel leaves you in. But although the sense that the book is a tragedy is inescapable, there are moments – as with all great tragedies – that leave you feeling that disaster can be averted, dreams and ambitions fulfilled, and happiness achieved. This is most apparent in the early chapter that features the ball at the chateau, an event that sets the kindling of Emma Bovary's nascent dreams ablaze. It is the high point of Emma's life, and as such Flaubert's powers of description must be up to the ascent. If we are to feel with Emma, to sympathise - as well as get annoyed and angry at her self-deception, stupidity and cruelty - the ball must linger in our own memories for the rest of the story. It is a sensational piece of writing, conjuring up a thrilling luxuriousness that engulfs you and drags you right into the heart of Emma's consciousness.

Emma, on entering, felt herself wrapped round as by a warm breeze, a blending of the perfume of flowers and of the fine linen, of the fumes of the roasts and the odour of the truffles. The candles in the candelabra threw their lights on the silver dish covers; the cut crystal, covered with a fine mist of steam, reflected pale rays of light; bouquets were placed in a row the whole length of the table; and in the large-bordered plates each napkin, arranged after the fashion of a bishop’s mitre, held between its two gaping folds a small oval-shaped roll. The red claws of lobsters hung over the dishes; rich fruit in woven baskets was piled up on moss; the quails were dressed in their own plumage, smoke was rising; and in silk stockings, knee-breeches, white cravat, and frilled shirt, the steward, grave as a judge, passed between the shoulders of the guests, offering ready-carved dishes and, with a flick of the spoon, landed on one’s plate the piece one had chosen. On the large porcelain stove inlaid with copper baguettes the statue of a woman, draped to the chin, gazed motionless on the crowded room. Madame Bovary noticed that many ladies had not put their gloves in their glasses.

Emma isn't in her tiny village anymore. Ladies putting their gloves in their glasses and signalling their abstention from alcohol is the behaviour of the timidly provincial. Emma will certainly be having a drink tonight and revelling in what is the finest meal in literature. Flaubert doesn't merely describe what's on offer here, he brings it before us. The light, the smells, the warmth, the way food is made extraordinary and how it is presented. A 'flick of the spoon', the shape of the napkins, the truffles and quails and lobster. I can't even eat lobster without thinking of this passage. I'm not even sure I like lobster that much, but like Emma I'm vain enough to sometimes plump for the symbol over the reality.

All the chimeric impressions that the dish leaves upon Emma - luxury, glamour, bounty, style – at the moment of reading, I feel them too. Indeed, when Flaubert famously declared 'Madame Bovary c'est moi!', he is also suggesting she is us too. A lesser writer would have lit up these passages and the ball with an overbearing portentousness. But our empathy, which will be strained as the novel progresses, is not to be trifled with here. We are at the chateau too, and we are loving it.

Which means, that when Emma falls, we fall with her. The descent follows immediately, albeit, to begin with, it is a gradual one. A rereading also flags up, that as well as being the great novel of adultery and disappointment, Madame Bovary is also the great novel of irritation. Just as no one can touch Marcel Proust on the subject of jealousy, nobody writes of irritation like Flaubert. It's here that Emma really begins to test our sympathy. Charles Bovary lacks imagination, is complacent and compared to the denizens of the ball is dull. Yet we are all too ready to share in the irritability that Emma feels towards her husband.

"What a man! what a man!" she said in a low voice, biting her lips. She was becoming more irritated with him. As he grew older his manner grew coarser; at dessert he cut the corks of the empty bottles; after eating he cleaned his teeth with his tongue; in eating his soup he made a gurgling noise with every spoonful; and, as he was getting fatter, the puffed-out cheeks seemed to push the eyes, always small, up to the temples.

It's the tiny little things that are often the most damning. And as a noisy eater, I wince self-consciously when I read this passage.

Rereading the novel's most controversial passages did not blunt their power. The famous carriage scene, the one where Emma and Leon spend most of the day consummating their adulterous relationship (Emma's second act of adultery) unsurprisingly caused huge outrage at the time. Perhaps though, the greater controversy was what went before, the scene of the lovers' rendezvous in Rouen Cathedral.

Leon walked solemnly alongside the walls. Life had never seemed so good to him. She would soon appear, charming and agitated, looking back to see if anyone was watching her — with her flounced dress, her gold eyeglass, her delicate shoes, with all sorts of elegant trifles that he had never been allowed to taste, and with the ineffable seduction of yielding virtue. The church was set around her like a huge boudoir; the arches bent down to shelter in their darkness the avowal of her love; the windows shone resplendent to light up her face, and the censers would burn that she might appear like an angel amid sweet-smelling clouds.

Recently, in the second series of the magnificent Fleabag there was another scene that caused a stir, where a foul-mouthed and lovelorn priest demanded that the heroine kneel before him in his church – outside of the confessional, no less - and perform fellatio. A statue falling from the altar put a stop to the act. Many laughed, and some even thought the scene quite sexy. A sizeable number were outraged. But as Madame Bovary proves, there's nothing shockingly new here. Leon's comparing of one of the most famous cathedrals in the world to a 'huge boudoir' is no casual metaphor. In fact the whole building is made to seem complicit in their sinful union. It would have shocked Nineteenth-century France just as much as Fleabag outraged Catholic sensibilities today. And lest we think churches and sex don't mix, we might want to take a glance at their exterior walls. Even closer to home, one can find magnificent Sheela-na-gigs adorning many of the most conservative parishes of Middle England. Take that, Anne Widdecombe! One of Christianity's foundational tenets might have always been to keep your lustful thoughts away, but the truth has always been to keep them not too far away.

My rereading of Madame Bovary does, of course, need qualifying. I'm reading in translation. My sluggishness and lack of perseverance with French – or any other language – is shameful. But I'm confident – or as confident as I can be – that I'm getting close to the total impact of a great work of art. The story of Flaubert's tragic heroine flicks the switches of all the emotions. You want Emma Bovary to triumph but also know that she must not. She is selfish, vain, often ridiculous, and worst of all cruel; she is also brave, resourceful, and above all wonderfully imaginative. Reading Flaubert's final masterpiece Bouvard and Pécuchet recently, really highlighted just how wonderful Flaubert is at giving you characters that leave you flailing in any attempt solid attempts at unequivocal evaluation. You find yourself sympathising and damning them in the space of a single sentence. Above all, you sense that their vanities and motives, and, of course, their weaknesses, are oh so close to your own. Madame Bovary c’est nous!

|

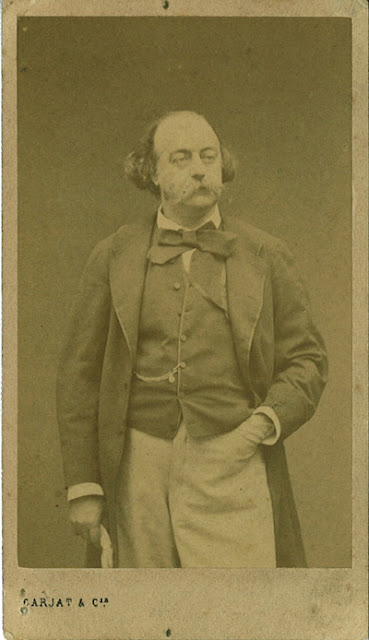

| Gustave Flaubert |

That last remark is, perhaps, borne out of the mood that the novel leaves you in. But although the sense that the book is a tragedy is inescapable, there are moments – as with all great tragedies – that leave you feeling that disaster can be averted, dreams and ambitions fulfilled, and happiness achieved. This is most apparent in the early chapter that features the ball at the chateau, an event that sets the kindling of Emma Bovary's nascent dreams ablaze. It is the high point of Emma's life, and as such Flaubert's powers of description must be up to the ascent. If we are to feel with Emma, to sympathise - as well as get annoyed and angry at her self-deception, stupidity and cruelty - the ball must linger in our own memories for the rest of the story. It is a sensational piece of writing, conjuring up a thrilling luxuriousness that engulfs you and drags you right into the heart of Emma's consciousness.

Emma, on entering, felt herself wrapped round as by a warm breeze, a blending of the perfume of flowers and of the fine linen, of the fumes of the roasts and the odour of the truffles. The candles in the candelabra threw their lights on the silver dish covers; the cut crystal, covered with a fine mist of steam, reflected pale rays of light; bouquets were placed in a row the whole length of the table; and in the large-bordered plates each napkin, arranged after the fashion of a bishop’s mitre, held between its two gaping folds a small oval-shaped roll. The red claws of lobsters hung over the dishes; rich fruit in woven baskets was piled up on moss; the quails were dressed in their own plumage, smoke was rising; and in silk stockings, knee-breeches, white cravat, and frilled shirt, the steward, grave as a judge, passed between the shoulders of the guests, offering ready-carved dishes and, with a flick of the spoon, landed on one’s plate the piece one had chosen. On the large porcelain stove inlaid with copper baguettes the statue of a woman, draped to the chin, gazed motionless on the crowded room. Madame Bovary noticed that many ladies had not put their gloves in their glasses.

Emma isn't in her tiny village anymore. Ladies putting their gloves in their glasses and signalling their abstention from alcohol is the behaviour of the timidly provincial. Emma will certainly be having a drink tonight and revelling in what is the finest meal in literature. Flaubert doesn't merely describe what's on offer here, he brings it before us. The light, the smells, the warmth, the way food is made extraordinary and how it is presented. A 'flick of the spoon', the shape of the napkins, the truffles and quails and lobster. I can't even eat lobster without thinking of this passage. I'm not even sure I like lobster that much, but like Emma I'm vain enough to sometimes plump for the symbol over the reality.

|

| Still Life With A Lobster, Willem Claesz (1650) |

All the chimeric impressions that the dish leaves upon Emma - luxury, glamour, bounty, style – at the moment of reading, I feel them too. Indeed, when Flaubert famously declared 'Madame Bovary c'est moi!', he is also suggesting she is us too. A lesser writer would have lit up these passages and the ball with an overbearing portentousness. But our empathy, which will be strained as the novel progresses, is not to be trifled with here. We are at the chateau too, and we are loving it.

Which means, that when Emma falls, we fall with her. The descent follows immediately, albeit, to begin with, it is a gradual one. A rereading also flags up, that as well as being the great novel of adultery and disappointment, Madame Bovary is also the great novel of irritation. Just as no one can touch Marcel Proust on the subject of jealousy, nobody writes of irritation like Flaubert. It's here that Emma really begins to test our sympathy. Charles Bovary lacks imagination, is complacent and compared to the denizens of the ball is dull. Yet we are all too ready to share in the irritability that Emma feels towards her husband.

"What a man! what a man!" she said in a low voice, biting her lips. She was becoming more irritated with him. As he grew older his manner grew coarser; at dessert he cut the corks of the empty bottles; after eating he cleaned his teeth with his tongue; in eating his soup he made a gurgling noise with every spoonful; and, as he was getting fatter, the puffed-out cheeks seemed to push the eyes, always small, up to the temples.

It's the tiny little things that are often the most damning. And as a noisy eater, I wince self-consciously when I read this passage.

Rereading the novel's most controversial passages did not blunt their power. The famous carriage scene, the one where Emma and Leon spend most of the day consummating their adulterous relationship (Emma's second act of adultery) unsurprisingly caused huge outrage at the time. Perhaps though, the greater controversy was what went before, the scene of the lovers' rendezvous in Rouen Cathedral.

Leon walked solemnly alongside the walls. Life had never seemed so good to him. She would soon appear, charming and agitated, looking back to see if anyone was watching her — with her flounced dress, her gold eyeglass, her delicate shoes, with all sorts of elegant trifles that he had never been allowed to taste, and with the ineffable seduction of yielding virtue. The church was set around her like a huge boudoir; the arches bent down to shelter in their darkness the avowal of her love; the windows shone resplendent to light up her face, and the censers would burn that she might appear like an angel amid sweet-smelling clouds.

|

| The Nave at Rouen Cathedral |

Recently, in the second series of the magnificent Fleabag there was another scene that caused a stir, where a foul-mouthed and lovelorn priest demanded that the heroine kneel before him in his church – outside of the confessional, no less - and perform fellatio. A statue falling from the altar put a stop to the act. Many laughed, and some even thought the scene quite sexy. A sizeable number were outraged. But as Madame Bovary proves, there's nothing shockingly new here. Leon's comparing of one of the most famous cathedrals in the world to a 'huge boudoir' is no casual metaphor. In fact the whole building is made to seem complicit in their sinful union. It would have shocked Nineteenth-century France just as much as Fleabag outraged Catholic sensibilities today. And lest we think churches and sex don't mix, we might want to take a glance at their exterior walls. Even closer to home, one can find magnificent Sheela-na-gigs adorning many of the most conservative parishes of Middle England. Take that, Anne Widdecombe! One of Christianity's foundational tenets might have always been to keep your lustful thoughts away, but the truth has always been to keep them not too far away.

|

| "Sheela-na-gig, Sheela-na-gig, you exhibitionist!" |

My rereading of Madame Bovary does, of course, need qualifying. I'm reading in translation. My sluggishness and lack of perseverance with French – or any other language – is shameful. But I'm confident – or as confident as I can be – that I'm getting close to the total impact of a great work of art. The story of Flaubert's tragic heroine flicks the switches of all the emotions. You want Emma Bovary to triumph but also know that she must not. She is selfish, vain, often ridiculous, and worst of all cruel; she is also brave, resourceful, and above all wonderfully imaginative. Reading Flaubert's final masterpiece Bouvard and Pécuchet recently, really highlighted just how wonderful Flaubert is at giving you characters that leave you flailing in any attempt solid attempts at unequivocal evaluation. You find yourself sympathising and damning them in the space of a single sentence. Above all, you sense that their vanities and motives, and, of course, their weaknesses, are oh so close to your own. Madame Bovary c’est nous!

Thank you must read again soon !

ReplyDeleteI don’t think there’s any sympathy to be had towards Emma Bovary. She’s not a sympathetic character at all, just loathsome and selfinterested. It’s a great novel though and Flaubert is essentially savaging her.

ReplyDelete