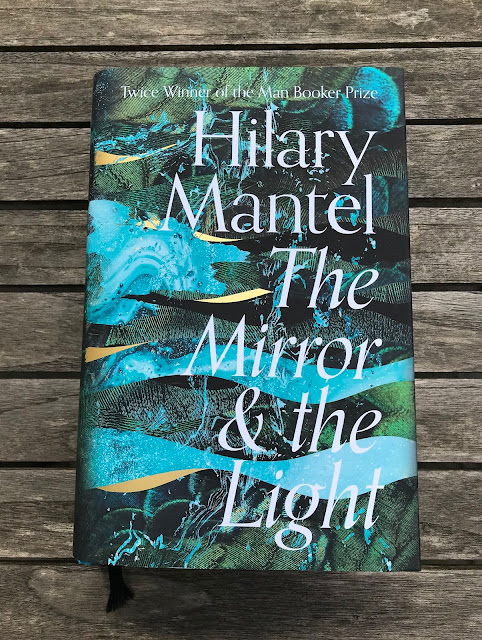

Hilary Mantel's The Mirror and the Light

Here's a tip, and something of a spoiler - the latter only if you're slightly ridiculous about your reading. Read the final seven pages of Hilary Mantel's The Mirror and the Light first thing in the morning, and the preceding seven pages the evening before. I might also suggest playing the opening Adagio from Beethoven's String Quartet No.14 - mournful and suitably resigned - but you may prefer a complementary silence, an uneasy hush that befits spending your last night alive in a gloomy cell in The Tower of London.

It's the timing that is important. Mantel's third-person historical present account, with glorious flashbacks channelled through five decades of memory, almost demands that you go to sleep - or try to - and wake up with Thomas Cromwell on the morning of his execution. After all, and particularly if you're a slow reader like I am, you've probably devoted around two months of your life to reading the three magnificent books that make up the Wolf Hall trilogy. And furthermore, reading over a decade or so adds to the impulse to slow and savour as you approach the axe. The trilogy has created ghosts, and now the consciousness that has been tracked throughout, will take its own place in that gallery of spectres.

Amongst many things, Mantel's trilogy is about class and the ghosts that accompany it. You can leave your roots but you can never totally escape them. Cromwell is low-born, the son of a brutish Putney blacksmith, yet he rises to the position of the second most powerful man in England. And whilst his enemies never let him forget those lowly beginnings, neither does his own conscience. In the frequent moments that we find Cromwell attempting to assess the situation, to take stock, he is haunted by the ghost of himself. Indeed, to attempt to look into the future, you always need to look back too.

That night he prays and goes to bed early ... He needs a space in which he can watch the future shaping itself, as dusk steals over the river and the park smudges the forms of ancient trees: there are nightingales in the copses, but we will not hear them again this year. Tomorrow, all eyes will turn, not to the Garter stall he fills, but to the vacancy, where a prince as yet unborn reaches for the statute book, and bows his blind head in its caul. Why does the future feel so much like the past, the uncanny clammy touch of it, the rustle of bridal sheet or shroud, the crackle of fire in a shuttered room? Like breath misting glass, like water, like scampering feet and laughter in the dark ... furiously, he wills himself into sleep. But he is tired of trying to wake up different. In stories there are folk who, observed at dusk and dawn in some open, watery space, are seen to flit and twist in the air like spirits, or fledge leather wings through their flesh. Yet he is no such wizard. He is not a snake who can slip his skin. He is what the mirror makes, when it assembles him each day. Jolly Tom from Putney. Unless you have a better idea?

The ghosts of the past. They are everywhere in this novel. There's even a small section for them in the 'Cast of Characters' at the start: 'The recently dead'. But the list extends far beyond a few of Anne Boleyn's alleged lovers. Cromwell's father Walter, and the man who helped Cromwell rise, Cardinal Wolsey are the most ubiquitous; but we also get Thomas More; Katherine of Aragon and her successor; the hapless Eel boy who, unwisely, taunted Cromwell as a child; burned heretics whose smell and taste invade the present; Flemish patrons and Italian bankers; chefs and kitchen hands; and long-gone lovers taking a day-trip to view the Ghent Altarpiece. You plan for the future, but always with the memory of the dead. Unsurprising then, that these books and their affirmation that memory stands independent of time, would often have me reaching for the famous lines that begin Four Quartets, and not just because of the irony inherent in T.S. Eliot's excavation of Anglo-Catholicism: 'Time present and time past / Are both perhaps present in time future, / And time future contained in time past.' Mantel's Cromwell would surely have enjoyed that poem.

|

| Hans Holbein the Younger's Portrait of Thomas Cromwell (1532) |

What might be missed in my remarks above, and perhaps because of my tardy reading speed, is what fantastic page-turners these novels are. You slow for certain passages, such as the one quoted, but the conversations which dominate the trilogy career forward with wit, gravitas and momentum. And what a cast. You develop an attachment to certain characters and you fizz with anticipation when they stride onto the page. Mary, the King's first daughter: surly, sickly, ostracised, but bursting with religion and foreboding; one of Cromwell's many enemies, Thomas Howard, ridiculous and rough mannered, dismissing a theological marriage nicety with an anachronistic 'Bollocks!'; his niece, Katherine Howard, a giggling and cheeky adolescent, doomed by Mantel's very first description. And those who never materialise before Cromwell, yet impact on his actions and life: the King of France, the Emperor Charles, and, waiting and manipulating in the wings of the Vatican, Reginald Pole (I last encountered Pole in my reading life as a late protagonist in Luther Blissett's Q).

|

| Hans Holbein the Younger's Portrait of Anne of Cleves (1539) |

In particular, the sections of the novel that deal with Henry's ill-fated marriage (aren't they all, Catherine Parr aside) to Anne of Cleves are quite brilliant. From the controversy over Holbein's portrait, to the imagined meeting, to the fall-out which comes crashing down on Cromwell himself, these sections of The Mirror and the Light dance across a tightrope of rumour and subjectivity, masculine depravity and prurience, and a surprising sensitivity. I feel that a lesser writer than Mantel would have gone full-on tabloid in these sections, and it is to her artistic credit that we feel that we are perhaps close to some kind of truth.

And above all these characters, there is Henry himself. This is not a particularly original thought, but it bears rehearsing: you cannot help – reading this in 2020 – but compare Henry's tyrannous caprices and vacillations to those of Donald Trump. The White House is the Tudor Court; less savage perhaps, but still a dangerous lottery of a workplace. Relax and rest on laurels at your peril. Cromwell's final elevation to the 'position' only moves him closer to the chopping-block.

Both Lords and Commons might have been astonished that a man made an earl in

April is by June kicked out like a dog who’s stolen the beef. But then,

Parliament men do not expect to understand the king’s mind. He does not answer

for himself downwards, to his subjects – only upwards, to the Almighty; and

perhaps, these days, not even that. To hear Henry talk, you would think God

ought to be grateful, for all Henry had done for him in England these last ten

years: the way he’s set him up, got his big book translated, made him the

common talk.

|

| After Hans Holbein the Younger, Portrait of Henry VIII (original 1536) |

There's judgements aplenty above - direct and oblique. But one is missing. What of Thomas Cromwell? If Mantel's wonderful and majestic depiction is only half-true, I certainly would not have been too keen on coming into his ken, let alone spending a night in a cell with him. Yet, what stays with me as I place this huge tome on my bookshelf is his occasional kindness, particularly to his family, his thoughtfulness, his restless curiosity. Ultimately, though, like Henry, the 'mirror and light to all princes', and therefore reflecting and shining that example down onto Cromwell, he too was a monster, prepared to knowingly send innocents to their doom. Hilary Mantel is now free to write something different. I do hope she stays with monsters. There is no one better at portraying them.

Comments

Post a Comment