A. L. Reynolds' Welsh Love Story - Of The Ninth Verse

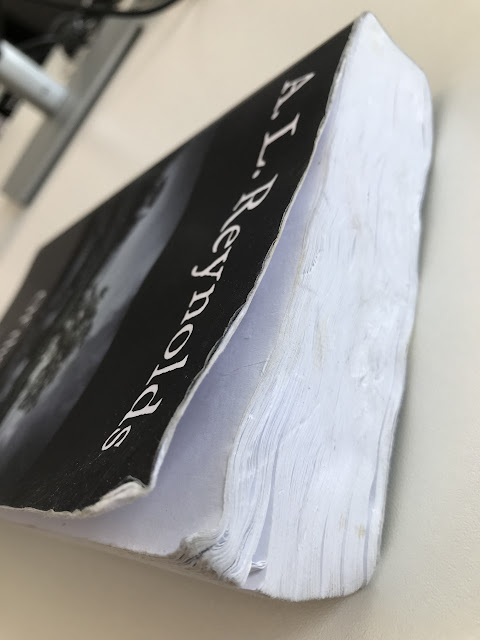

I dislike having flasks or bottles of liquid in my rucksack. No matter how carefully I screw on the lid, there is eventually a mishap and everything gets soaked. The last victim of a deluge was Welsh author A.L. Reynolds' novel Of The Ninth Verse. Initially the damp pages looked set to dry, but then, inevitably, they warped and smudged and the satisfying rectangular tactility that comes with picking up a book was lost. The author was in very fine company though. It was Vladimir Nabokov and Ada and Ardor all over again, another casualty of bag-bottle carelessness. And in dwelling upon this I sensed a startling coincidence. Thematically, both of those novels deal, in very different ways, with the subject of incestuous love.

I've already written about Nabokov's most difficult book, but it's interesting to compare how these two writers approach this taboo. Although approach may not be the right word for Nabokov: the impression that he leaves you with is that filial incest is a mere prop, enabling him to light literary fireworks and dazzle and divert the reader with explosive trickery.

Reynolds' method, however, is one of empathy and exploration, conveyed in a sharp, lucid prose that treads a tricky balance between compassion and directness. Her story is that of Anwen and Idwal, sister and brother, who gradually embark upon a sexual relationship amidst the confines of their parents' Welsh mountain farm. There's a bluntness to that description, though, that does not do justice to the sensitivity of the story. Or, indeed, in the way that it is told.

Again - as the warped pages won't let me forget - I find myself returning to Nabokov. No one writes about butterflies and moths like him. Nor should anybody try. Yet I could not help comparing the quality and playfulness of the following passage to the Russian's unmatched lepidoptery flights. Anwen has been working in the fields, holding fence-posts for Idwal to hammer into the ground. She is now resting back at the farmhouse.

Her shoulders ached, and the bones of her hands were sore from the percussion of hammer blows. She was sunburnt again, and her head was throbbing and her tongue felt dry in her mouth. But she lay back on her bed in the still heat of the night, and felt content. Moths flew in from the night air and butted blindly at the light bulb, their wings too much of a blur to see. And they fluttered against the upper pane of the sash window like jewels in the night – white ones with ermine ruffs and turquoise ones with tiny wings and bright orange bugs with searching antennae – and then a cockchafer, speeding in with urgent purpose like a fat fighter aeroplane, its wings whirring and chattering.

There is a delicate and lyrical sensuality here that is then daringly undercut by the blunt and mischievously comic double-entendre that signals the approach of Anwen's brother and lover to the bedroom. That you are able to pick up on these subtleties, and sense the delicate shifts of tone and register, surely means that you have bought into this forbidden love affair.

|

Like Nabokov, Reynolds also has the ability to carve out a dazzling image or metaphor. A low, long farmhouse in the valley is like 'a cat sleeping in a place of safety, in a dip in the quilt'. Post-coital hips are 'as relaxed as warm toffee'. And in a passage that sent me immediately to the kitchen to grab toast, the process and impact of making marmalade is lovingly described and then the product itself is spread 'thicker than cut cheese'.

She looked back to her toast, the butter melted into the brown surface and marmalade spread lightly over the top. She took a bite, and let the bittersweet taste sink about her tongue. She remembered the marmalade being made, last year when outside was all sunshine and happiness and her mother standing by the stove stirring the bubbling mass of oranges and sugar with a long wooden spoon, and checking the jam thermometer every few minutes. The whole house had smelt of boiling marmalade – it was in the curtains and the carpets, wafting up the stairs and through the open doors. The smell turned her stomach – but once it was cool and jarred and here to spread on her toast in the early morning it was delicious.

However, there's far more to this novel than gentle, deflecting lyricism. The grander questions are not shirked, as metaphysics and art are brought effortlessly and seamlessly into the foreground. Sex and its always fascinating confrontation with religion are embraced. My favourite passage in the book finds Anwen attempting to reconcile the sin of loving her brother with the rightness of how that sin feels.

It all seemed so natural when they were alone – it seemed so beautifully, simply natural. To act on one’s desire, to slip into the water when it was warm and calm, to eat the fruit that was ripe and ready to pick. The electricity that sparked between their fingers was perfect and true…

She thought of God creating Adam on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. She thought of that majestic moment condensed into a tiny flash of light. Was that the soul entering the body? Was the soul created by love? Perhaps she had been wandering soulless until that moment when a touch had exploded into a frenzy of sensation that set her nerves and her mind aflame. God the father had created the son in an orgasm of terrifying joy. She felt like that. She felt as if she had been searching with her eyes closed – and then she had looked, and seen Idwal.

And then Eve…

She thought of Eve, taken from the ribcage of the child of God, blood of blood and bone of his bone, sister to his brotherhood, wife to his manhood, daughter to the same father to whom Adam was born…

Eve, with her dark glinting eyes and her perfect body, who had found love and lust combined in the presence of her own brother.

Oh, it was so natural, to lie in Eden with one’s brother and explore him like a new land, like a world new-create… Her fingertips tingled with his touch…

It's easy to sense a self-serving sophistry at work in Anwen's justifications here. Yet, isn't that the only way to negotiate the Church and its contradictions? In a theodical sense, it's the only way that the Church itself can possibly manage it. If God loves us and is all powerful, why then do we have evil? Why then do we fall in love with our brother?

|

| Michelangelo, The Creation of Adam |

I love Reynolds' use of ellipsis in this passage, and as I read and imagine that famous ceiling, those horizontal dots take on the appearance of 'electricity sparked between fingers': thoughts reaching out and striving to rationalise. Michelangelo's masterpiece also had me thinking about a later episode in the novel - and this might have much to do with my working at a university and being present at numerous graduation ceremonies - where Anwen, unable to physically attend her degree ceremony, will not be granted her full and proper degree. That practise may no longer be the case, but still, the reaching out of a Vice-Chancellor's hand to a graduating student - the moment that the degree is bestowed - might well have its antecedents in ecclesiastical arrogance, the desire, as in that hand in the centre of the ceiling, to play God.

For all its drama and sense of foreboding, Of the Ninth Verse is a strangely comforting read. And it is so much more than a novel about an illicit relationship. Reynolds is glorious on the subject of grief and life in the Welsh hills, and there is an Heaneyesque quality in her descriptions of the landscape where she, indeed, lives. The passages on marmalade, and the winding of clocks, and the radio merit reading over and over again.

But for me, it is the compassion and daring authenticity of

the story that stays with you. And it was that thought that sent me back, once

again, to Nabokov and the recollection of the strange and overly-provocative

line that sullies the cover of my copy of Lolita. Ascribed to Vanity Fair

magazine is the blurb that describes the novel as 'the only convincing love

story of our century'. Now Lolita is many things: sensational, unsettling,

dazzling and utterly unforgettable. But it is no love story, rather the

incredibly 'fancy prose style' of a paedophile. Of The Ninth Verse is a love

story. And a compassionate and incredibly convincing one at that.

Comments

Post a Comment