'Fled is that music' - Baz Luhrmann's Keats-free Gatsby

'What men or gods are these? What maidens loth?

What mad pursuit? What struggle to escape?

What pipes and timbrels? What wild ecstasy?

Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard

Are sweeter ...'

John Keats, 'Ode on a Grecian Urn'

*

Back in 2012, I recall getting very excited at the announcement that Baz Luhrmann was filming a new version of F. Scott Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby. If anyone could conjure up the party to end all parties, it was certainly the director responsible for the giddy and debauched Moulin Rouge. But after an hour or so, I started to feel uneasy. And by the time the film hit the cinemas, and I'd seen the bouncy over-the-top trailer, I just felt queasy. That I would also have had to don a pair of irritating 3D-glasses to feel the maximum benefit of Luhrmann's fireworks and glitz meant that I wasn't going to be finding my way to Gatsby's West Egg mansion via a West End cinema.

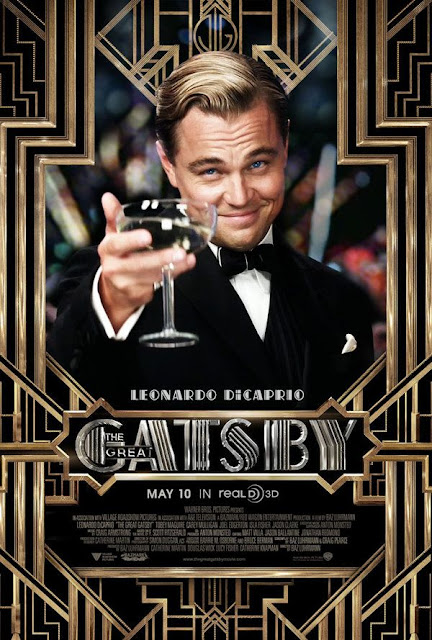

Lockdown provides plenty of space to catch up, and that the surprise of finding out that the ubiquitous photographic meme of Leonardo DiCaprio toasting onlookers wasn't a still from The Wolf of Wall Street, but rather the actor's portrayal of Jay Gatsby, reminded me that I'd not yet seen the film. Time to give it a go then.

Seeing an adaptation of a piece of literature that you love is inevitably going to make you feel apprehension. And I'm all too aware that a willingness to temporarily disinvest from the original work is vital if you're going to give yourself any chance of enjoying it. Nevertheless, if a director is going to take on one of the greatest novels of the twentieth century - indeed, if he's going to call his film The Great Gatsby - he's got artistic responsibilities. Certain moments must be included. By all means, bring in an anachronistic soundtrack - Jay-Z and Lana del Rey are more than welcome at this party - but don't dare drop the kind of keystone line that holds the whole story together. I am, of course, talking about Gatsby's description of the voice of Daisy, the woman that he loves. Nick Carraway, the novel's narrator muses on this voice with Gatsby:

"She's got an indiscreet voice," I remarked. "It's full of -" I hesitated.

"Her voice is full of money," he said suddenly.

That was it. I’d never understood before. It was full of money – that was the inexhaustible charm that rose and fell in it, the jingle of it, the cymbals’ song of it.

It is ambiguous, beautiful and crucial. And it does not make it into the film. There is so much going on in this short exchange. Nick's interpretation of what he thinks Gatsby is getting at; what we think Gatsby means by it; what we think of Nick's interpretation of Gatsby's remark. Is Gatsby delivering some waspish put down of the old-monied class, or does it carry a peculiar lyricism, one that peels away the vulgarity that we associate with money and, through sheer force of will, lifts it into the realm of the beautiful? Or, even, is it both? Perhaps this is the trick that the film can't pull off. And it is a trick: a seamless switch between the barbed and sardonic and a delicate lyricism.

Scott-Fitzgerald's novel is full of this lyricism: orchestra's 'playing yellow cocktail music'; 'air ... alive with chatter and laughter and casual innuendo and introductions forgotten on the spot and enthusiastic meetings between women who never knew each other's names'; drinks served on 'trays that float through the twilight'; wives that appear suddenly at their husband's sides like 'angry diamonds'; tears that smudge eye-shadow and create musical notations on a singer's cheek.

Words focus and still your attention. You are able to hone in on them and take them at your own pace. Scott Fitzgerald's sentences urge you to read them over and over again. But the fleet-footed visuals of film, particularly extravagant film, can overwhelm and drown out all subtlety. The novel is awash with extraordinary examples of synaestheisa; but in the film we are left only seeing the colour and not tasting that 'yellow cocktail music', or sensing the 'anger' in an inanimate diamond.

Some of this I am able to forgive. Luhrmann's handing of the novel's close is very good. The words - appearing on the screen and carefully voiced by Nick - are among the most powerful in American letters. They are fresh, powerful and impossibly sad.

Gatsby believed in the green light, the orgastic future that year by year recedes before us. It eluded us then, but that's no matter - tomorrow we will run faster, stretch out our arms farther . . . . And one fine morning - -

So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.

That famous green light. I'm glad that Luhrmann gives it such a prominent place in the film. Indeed, the first hint we get of Gatsby's fall and the slow, inevitable uncoupling from Daisy occurs as he and Nick stand on the end of the jetty gazing across the water to East Egg. The dialogue muddles its way into the film as does Nick's gooseberry commentary:

"If it

wasn't for the mist we could see your home across the bay," said Gatsby. "You always have a green light that burns at the end of your dock."

Daisy put her arm through his abruptly but he seemed absorbed in what he had just said. Possibly it had occurred to him that the colossal significance of that light had now vanished forever. Compared to the great distance that had separated him from Daisy it had seemed very near to him, almost touching her. It had seemed as close as a star to the moon. Now it was again a green light on a dock. His count of enchanted things had diminished by one.”

It would be remiss of me, particularly as this whole blog is named after a phrase in Keats' 'Ode to a Nightingale', and that today is also the two-hundredth anniversary of the poet's death, not to find strong thematic echoes of that poem in these lines and to note the gorgeously Keatsian cadences. Scott Fitzgerald remarked on a number of occasions that reading Keats, and particularly 'Ode to a Nightingale' (listen to the author recite - not quite word perfectly - from memory here) prepared him for the writing of Gatsby, his third novel and first masterpiece. For me, the novel and the poem are conducting a strange, dazzling dance. Take a look at how the final stanza of the poem mirrors the above passage on the the vanishing green light:

Daisy put her arm through his abruptly but he seemed absorbed in what he had just said. Possibly it had occurred to him that the colossal significance of that light had now vanished forever. Compared to the great distance that had separated him from Daisy it had seemed very near to him, almost touching her. It had seemed as close as a star to the moon. Now it was again a green light on a dock. His count of enchanted things had diminished by one.”

It would be remiss of me, particularly as this whole blog is named after a phrase in Keats' 'Ode to a Nightingale', and that today is also the two-hundredth anniversary of the poet's death, not to find strong thematic echoes of that poem in these lines and to note the gorgeously Keatsian cadences. Scott Fitzgerald remarked on a number of occasions that reading Keats, and particularly 'Ode to a Nightingale' (listen to the author recite - not quite word perfectly - from memory here) prepared him for the writing of Gatsby, his third novel and first masterpiece. For me, the novel and the poem are conducting a strange, dazzling dance. Take a look at how the final stanza of the poem mirrors the above passage on the the vanishing green light:

Forlorn! the very word is like a bell

To toll me back from thee to my sole self!

Adieu! the fancy cannot cheat so well

As she is fam'd to do, deceiving elf.

Adieu! adieu! thy plaintive anthem fades

Past the near meadows, over the still stream,

Up the hill-side; and now 'tis buried deep

In the next valley-glades:

Was it a vision, or a waking dream?

Fled is that music:- Do I wake or sleep?

There might only be one 'now' in this stanza, but it finds a repeated chime in Fitzgerald's prose: 'That light had now vanished forever … now it was again a green light on a dock'. At the exact moment that Gatsby's dream is coming to fruition it begins to die. Like Keats' bird, it is elusive, incompatible with workaday reality, and therefore, always just out of reach.

Taken entirely on its standalone merits, Luhrmann's Gatsby isn't a bad film. However, he fails dismally because he has willfully undertaken the challenge to adapt a great novel. It is a book that does not contain a superfluous word; there is not one single thought that isn't apposite to the whole. And with this choice, he sets himself too high a bar. In dropping key lines and not giving greater weight to the text - and he proved he could do that with the final act - he fails to even to give himself a fighting chance.

Is a definitive and faithful film version of Gatsby possible (I've not seen Jack Clayton's version starring Robert Redford, but the reviews are not great)? Who knows? To capture the bombast and the vulgarity of the parties, yet still retain the Keatsian lyricism, subtleties and ambiguity of the words would require a great artist. And what is needed is a director that can embrace and rise to the challenge of Scott Fitzgerald's famous aphorism: "The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time, and still retain the ability to function." Like Gatsby staring at the green light across the water, we can but hope. Like Gatsby, we'll probably be disappointed.

*

Postscript: Some digging reveals that Luhrmann actually filmed a 'voice full of money scene' but chose to cut it. His explanation - watch the scene and the director's remarks here - strikes me as cowardly and a dumbing down of the worst kind. And don't get me started on the fact that the scene twists the conversation into a direct commentary on Daisy's fidelity rather than an ambiguous and beautifully hazy bit of dialogue on the chimerical charm of money.

Comments

Post a Comment