Saint Maud - Art Colliding with Asceticism

What lifts a good horror film into the realms of greatness? For me it's style, a carefully thought out and controlled aesthetic that brings visually arresting, yet not overwhelming elements, right into the heart of the story. These elements should also be independent of moments of dread and shock, but also able, subtly, to complement them. Stanley Kubrick's The Shining is the perfect example of this: think of those hotel corridors, the garish decor, particularly those migraine-inducing carpets and the way they provide the perfect race-track for Danny and his go-kart. Rose Glass's incredible debut feature Saint Maud does just this.

We all know that The Overlook Hotel is a place that exudes evil. Yet we are drawn into those rooms and corridors and that ball-room, and any horror fan worth their salt would pay a small fortune to spend a night there. Amanda's home also carries the same paradoxical dynamic of repulsion and attraction. The various Art Deco wallpapers that adorn the bedroom and staircases create a singular sense of place, yet also draw you into the inner-lives of the characters living there. Contrasting Amanda's bedroom with Maud's illustrates this perfectly.

That over-the-top Art Deco pattern tells of a full and glorious life - parties, flings and hedonism - but it's an existence that is now fully in the past. Maud's room, in the same house, is lifeless. Look at the blanched mauve, those bland jagged lines - a half-hearted parody of Art Deco - topped with a prominent and incongruous crucifix. Indeed, Glass and her crew take such care with individual shots. It's an incredibly beautiful film and one that cries out to be seen at the cinema (is this, following the Bond example, why we had to wait so long to see it come onto streaming services)? No matter, it certainly justified my lockdown investment in a huge television.

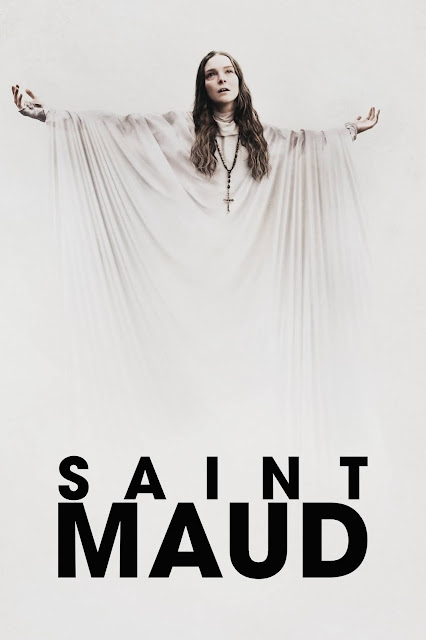

Like many ascetics, Maud has little time for beauty for beauty's sake. Yet, as if to emphasize the close lexical irony of aestheticism and asceticism, art - in the real sense - intrudes catastrophically into Maud's world (beware: spoilers ahead). When Amanda gifts Maud a book containing reproductions of William Blake's paintings and prints - perhaps a gesture hinting towards the beauty that the agnostic Amanda finds in religion - we sense trouble afoot. Blake's images, his radical theology, his sceptical relationship with more conventional strands of Christianity, are incredibly complex. Maud, with no time for the extraneous - no time to delve into the strange nuances of innocence and experience, good and evil - sees only what she wants to see. The voices in her head have taken her so far; the Blake paintings take her even further. Creating a shrine in her depressing bedsit after she has lost her job, cutting out the reproductions that strike her in the Blake book, she begins to plan. Her costume will be inspired by The Angels Hovering over the Body of Christ in the Sepulchre; later ecstatic gestures - look at the film's poster up above - will be taken from When the Morning Stars Sang Together.

|

| William Blake, The Angels Hovering over the Body of Christ (1805) |

And perhaps most tellingly, her death and self-immolation will be set in motion by A Naked Man In Flames. All of these works are visible in Maud's bedsit shrine and I'm sure Glass would have paid a visit to the recent William Blake exhibition (how many other artists, film-makers and writers have been inspired by that incredible show)?

|

| William Blake, A Naked Man In Flames (1804-1820) |

Although it rankles slightly, that whenever William Blake intrudes into the world of cinema, we invariably find his work employed on the side of darker forces - Francis Dolarhyde, 'The Tooth Fairy' in an Hannibal Lecter film styles himself 'The Red Dragon' and actually eats the Blake painting The Great Red Dragon and the Woman Clothed in the Sun (this painting also makes a fleeting appearance in Saint Maud) - it is still an absolute pleasure to see this great artist getting such broad exposure. We just need to learn to be better readers of his work than Maud.

Which brings me to my final bit of praise for Saint Maud. It is a strangely compassionate film. In fact, to argue against the grain of this piece, I'm not even sure it's an horror film. Although there are moments of unreality - voices, visions, levitation - we are quickly disabused of any supernatural elements, and it is made explicit that what we are seeing is the horrifically damaged interior of Maud's mind. Which perhaps makes it all the more alarming, the knowledge that this is the abyss that mental illness can, in its most extreme states, tumble into. We can't not pity her. Horror or not, what is certain is that Rose Glass has created a modern masterpiece. I cannot wait to see where this thirty-one year old goes next.

Thank you for helping people get the information they need. Great stuff as usual. Keep up the great work!!! Art deco wallpapers

ReplyDeleteThis is an excellent source of information, and I'll be coming to it frequently to learn more and extend my knowledge. Everyone, in my opinion, should be aware of it. Déco & Co Wallpaper

ReplyDelete