Daniel Defoe's Caution - Coronavirus Blues (IV)

It's either the perfect time to read Daniel Defoe's A Journal of the Plague Year, or it's the worst. As an inveterate hypochondriac, I should probably have kept the book quarantined. But the wonderful Guardian journalist Marina Hyde, in a piece that found her grabbing the book from her shelves and drawing parallels with the world's reaction to the Coronavirus, did for me.

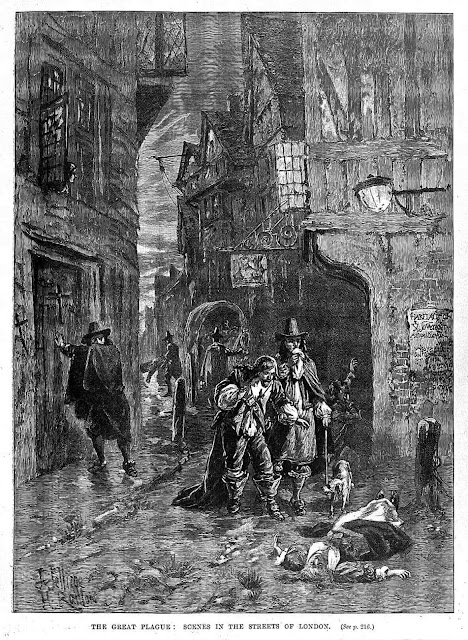

It is a remarkable book, and one that gains an obvious piquancy when read in the current climate. Defoe's story of the Great Plague of 1665 is brimming with mortality rates that rise exponentially, social distancing that leaves the streets of a great metropolis eerily quiet, and enforced isolation - thankfully, we haven't yet reached the stage where buildings housing those suffering from the plague are boarded up and policed by watchmen.

Amidst all of this, though, are moment of heroism and kindness, as ordinary people place their own lives at risk in looking out for their fellow man. Dutiful aldermen and constables remain in the city of London after thousands have fled to the relative safety of the countryside; members of the clergy stay right at the heart of the madness and carry on administering to their flocks; poor citizens are still available to take on the most dangerous tasks such as pushing the dead carts towards plague pits, and river-men take boats laden with their supplies out to ships at quarantine on the Thames. These, rather than the frightening parallels of a terrified city shutting down, are what left the biggest impression on me. You cannot help but compare them to the heroism displayed by the skeleton crews that remain in place and are keeping the country ticking over: the doctors and nurses in the NHS; the police, fire-crews and ambulance drivers in the emergency services; and the shopkeepers, supermarket staff and delivery drivers that are keeping us fed.

One hopes that this goodwill and esteem - particularly towards the NHS - will still be firmly in place when this is all over. It is far from guaranteed. Defoe's gently didactic narrator throws a caution our way, outlining how the factions in his own society were quick to return:

'It was not the least of our misfortunes, that with our infection, when it ceased, there did not cease the spirit of strife and contention, slander and reproach, which was really the great troubler of the nation’s peace before. It was said to be the remains of the old animosities which had so lately involved us all in blood and disorder; but as the late act of indemnity had lain asleep the quarrel itself, so the government had recommended family and personal peace, upon all occasions, to the whole nation.

But it could not be obtained; and particularly after the ceasing of the plague in London, when any one had seen the condition which the people had been in, and how they caressed one another at that time, promised to have more charity for the future, and to raise no more reproaches,—I say, any one that had seen them then would have thought they would have come together with another spirit at last. But, I say, it could not be obtained. The quarrel remained, the Church and the Presbyterians were incompatible. As soon as the plague was removed, the dissenting ousted ministers who had supplied the pulpits which were deserted by the incumbents, retired. They could expect no other but that they should immediately fall upon them and harass them with their penal laws; accept their preaching while they were sick, and persecute them as soon as they were recovered again. This even we that were of the Church thought was hard, and could by no means approve of it.

But it was the government, and we could say nothing to hinder it. We could only say it was not our doing, and we could not answer for it.'

Defoe's narrator may well be focusing his own attentions onto religious issues - the Established Church of England versus those who dissented from the Act of Uniformity of 1662 - but the warning is still apposite. The 'spirit of strife and contention, slander and reproach' that has dogged this country for the past four years, will surely return. And though the spectre of Brexit will no doubt rise again, and on that we'll surely still be at loggerheads, let's not allow issues such as the funding and staffing of the NHS to be forgotten, or - as before - apathetically pushed aside. If one good thing comes out of this virus, it is that we can never again be complacent about those who look after our health. And indeed, unlike the majority of 17th Century England, we do have the power to hinder the government. Let's make sure that every last one of us holds them to account on that.

Comments

Post a Comment