Tennyson and The Elephant Man - Coronavirus Blues (III)

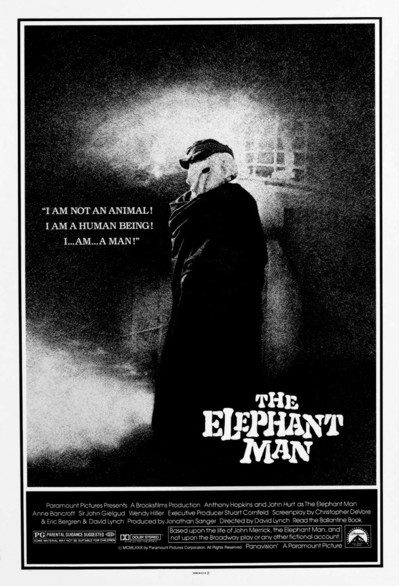

Rewatching the final moments of The Elephant Man, and the scene where the misnomered John Merrick (his real name was Joseph) takes to his bed for for the last time and we hear his mother narrate a poem over the top of Samuel Barber's 'Adagio for Strings', brought to mind an amusing outburst from an A Level English Literature teacher. We were discussing Tennyson and sentimentality - in David Lynch's film, the poem 'Nothing Will Die' is an early, throwaway effort by the eminent Victorian - and our teacher, trying to tease out a response to Tennyson's mawkish 'As thro' the Land', suddenly gave up. "Why the fuck am I bothering ... if you can't see how terrible this is, you might as well fuck off home!"

Back then, I struggled with Tennyson and it was a few years before I began to form a favourable opinion of him, and indeed, to not only appreciate his extraordinary technical abilities, but also how he deliberately and ironically employed the sentimental to draw out complex themes. Let's take a glance at 'As thro' the Land' and see what caused Mr Fuck Off Home's ire:

As thro' the land at eve we went,

And pluck'd the ripen'd ears,

We fell out, my wife and I,

O we fell out I know not why,

And kiss'd again with tears.

And blessings on the falling out

That all the more endears,

When we fall out with those we love

And kiss again with tears!

For when we came where lies the child

We lost in other years,

There above the little grave,

O there above the little grave,

We kiss'd again with tears.

A husband and wife argue and then are reconciled after standing over their child's grave. Look at the cloying and unnecessary repetition of 'little grave', almost certainly what Mr Fuck Off Home was asking us to latch onto. It is an easy piece of A Level analysis. Therein, though, lies the problem. This 'song' is part of a much larger poem called 'The Princess', and these occasionally sentimental interludes are key to creating a contrast between a male-orientated world of heroic chivalry and, at the time, controversial ideas about female education and emancipation. Indeed, Ida, the poem's would-be heroine and princess, is often reminded through these songs that a woman's role is one of tenderness and remaining as a regressive help-mate to a man. That we did not have recourse in our selected text to the wider poem, and therefore could not really consider it in any examination, meant that we could not analyse the issue of sentimentality in any meaningful way.

Which brings me back to David Lynch. How does that final scene in The Elephant Man escape the clutches of sentimentality? Put simply, it doesn't. The whole film is sentimental, but we buy into it because we are unable to take our eyes (and sympathy) away from the story of a disfigured and cruelly treated man who is rescued from a 'freak show' and given a little kindness and comfort. And when we reach that final moment, it turns the sentimental factor, Spinal Tap-style, up to eleven: the twee drawings of children asleep on the wall of John Merrick's room and his desire to sleep like that (we know if he lies down in that manner his condition will cause him to die); the careful way he prepares for bed and death; the honing in on the cross of the cathedral that he has manufactured out of bits of cardboard; the gentle slip into Barber's 'Adagio for Strings'; the image of his mother's face hovering within a halo above his bed; and that awful poem 'Nothing Will Die':

When will the stream be aweary of flowing

Under my eye?

When will the wind be aweary of blowing

Over the sky?

When will the clouds be aweary of fleeting?

When will the heart be aweary of beating?

And nature die?

Never, oh! never, nothing will die;

The stream flows,

The wind blows,

The cloud fleets,

The heart beats,Nothing will die.

Lynch's chutzpah takes us beyond sentimentality; it overwhelms our faculties and we succumb. Like Ann Treves (the Doctor's wife) earlier in the film, we cannot hold out against this overwhelming story - "They have such noble faces!" mumbles John Merrick when he looks at the photographs of the Doctor's family, and Ann breaks down in tears (for me the strongest and most moving scene in the film).

When will the stream be aweary of flowing

Under my eye?

When will the wind be aweary of blowing

Over the sky?

When will the clouds be aweary of fleeting?

When will the heart be aweary of beating?

And nature die?

Never, oh! never, nothing will die;

The stream flows,

The wind blows,

The cloud fleets,

The heart beats,Nothing will die.

Lynch's chutzpah takes us beyond sentimentality; it overwhelms our faculties and we succumb. Like Ann Treves (the Doctor's wife) earlier in the film, we cannot hold out against this overwhelming story - "They have such noble faces!" mumbles John Merrick when he looks at the photographs of the Doctor's family, and Ann breaks down in tears (for me the strongest and most moving scene in the film).

Of course, Lynch is no stranger to sentimentality (take a look at how he juxtaposes melodramatic Brazilian soap opera with the main murder narrative in Twin Peaks, and, how close Angelo Badalamenti's unforgettable score sails towards muzak, but changes course at the very last moment with a sinister minor chord). In his later work, he uses it to lull us into a false sense of security, and then - less so in The Elephant Man, which nearly forty years on, doesn't feel Lynchian at all - wrong-foots us with either savagery or bamboozlement.

The film also got me pondering as to whether or not we are more susceptible to the sentimental at a time of crisis. In normal circumstances, the Victorians certainly seem overly sentimental; these are not normal circumstances, though. With mortality rates rising because of coronavirus, it seems easier to exercise a touch more cultural empathy for those who lived through a time when premature death - particularly amongst mothers and infants - was a frequent and unremarkable occurrence. Revisiting The Elephant Man, I was struck by how incredibly moving it was. Perhaps if I'd rewatched before the current crisis, I'd have had a more cynical reaction. Something more in line with the take in Richard Curtis's best film, The Tall Guy, which revolves around turning the story into an unintentionally hilarious musical - 'Take a deep breath, prepare for the worst ... the ugliest man in the Universe!'

The film also got me pondering as to whether or not we are more susceptible to the sentimental at a time of crisis. In normal circumstances, the Victorians certainly seem overly sentimental; these are not normal circumstances, though. With mortality rates rising because of coronavirus, it seems easier to exercise a touch more cultural empathy for those who lived through a time when premature death - particularly amongst mothers and infants - was a frequent and unremarkable occurrence. Revisiting The Elephant Man, I was struck by how incredibly moving it was. Perhaps if I'd rewatched before the current crisis, I'd have had a more cynical reaction. Something more in line with the take in Richard Curtis's best film, The Tall Guy, which revolves around turning the story into an unintentionally hilarious musical - 'Take a deep breath, prepare for the worst ... the ugliest man in the Universe!'

|

| 'Alfred Tennyson', Julia Margaret Cameron's photograph (1865) |

I wander what Mr Fuck Off Home would have made of The Elephant Man? In fact, I'd have loved to find out what he really thought of Tennyson; whether or not his vitriol was aimed at our tardiness in picking apart poetry, or if he was actually arguing that the poet was not first rate. And if it was the latter, I'd feel much more equipped in arguing for Tennyson's majesty, particularly in poems such as 'In Memoriam', 'Locksley Hall', 'Ulysses', 'The Lady of Shallot' and - as I've just now declared it, the great poem of social-distancing and self-isolation - 'Mariana'.

Comments

Post a Comment